Polio Will Leave This World Kicking and Screaming

Decades-Long Eradication Effort Will Ultimately Succeed But Not Without Challenges

Over the past decade, I’ve written extensively about polio eradication—enough that the Gates Foundation has twice invited me to interview Bill Gates, the effort’s largest funder. It’s time for an update.

In the world of polio eradication, the most exciting number is six. In 2021, there were just six cases of polio that occurred as a result of the wild poliovirus. Let me reiterate that there were just six cases in the entire world when just 40 years ago, the number was closer to 400,000 cases.

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative leads the effort to end polio. Members of the GPEI acknowledge Rotary International as the leader of the movement. The Gates Foundation is the primary funder. UNICEF and the World Health Organization are implementation partners. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control is also a player. The Global Vaccine Alliance, GAVI, recently joined, providing some critical synergy between other routine vaccinations and polio immunization.

Those six 2021 cases happened in Afghanistan and Pakistan, countries considered endemic, never having gone a meaningful period without cases, and in Malawi, which identified a case that experts genetically traced to Pakistan. This is a painful reminder that even in the United States, a polio outbreak is just an airplane ride away.

So far this year, four cases have been identified in three countries, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Mozambique, where the case that teams reported this week was traced back to the Malawi infection last year.

In most of these countries, Malawi being the exception, there are additional polio cases that result from immunizations. The oral polio vaccine developed by Albert Sabin and used in the developing world provides better protection against community spread than the injections first developed in the 1950s by Jonas Salk.

When I was a child, I received the Sabin vaccine on a sugar cube. In the Western world today, children typically receive the Salk injection. While it allows for an immunized person to spread the disease, that person won’t get it. Its most significant advantage is that the vaccine is derived from dead viruses and never mutates into infectious disease.

Sadly, the Sabin vaccine does mutate. In about 1 out of every two million doses, a child becomes contagious with the disease. It is rare that such a child is personally paralyzed by the shot, but the mutated virus begins to spread.

As a result, in 2022, there have already been 55 cases of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Mozambique—most of which have occurred in Afghanistan, apparently as a result of the disorder caused by the U.S. withdrawal last year.

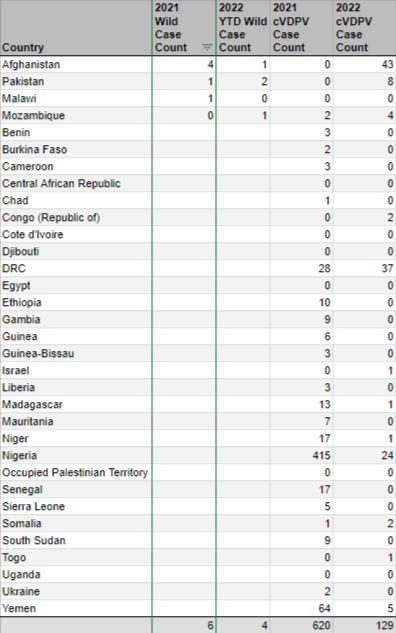

That, however, is just the tip of the iceberg. Around the world last year, there were 620 cVDPV cases reported. Nigeria reported most of those cases. The complete accounting is listed below.

As tragic and disturbing as the news of the cVDPV cases is, there is some closely related excitement around the solution.

When I spoke with Bill Gates the first time, we talked about a new vaccine he had authorized for development. Like the Sabin vaccine, it can be delivered via drops, making it easy for volunteers to provide quickly and safely. Unlike the Sabin vaccine, what is now called the novel oral polio vaccine won’t mutate.

When we spoke, regulators had not approved the vaccine. That has now changed, and health care workers are using the vaccine.

Because of its stability, it is the primary weapon against cVDPV outbreaks. Eventually, as production spools up, it could replace the Sabin vaccine completely.

Supply chain issues and other COVID effects are limiting production.

So far, 2022 is showing a lower transmission rate globally than 2021 for cVDPV. This may be a result of the implementation of the novel vaccine.

When people learn of the cVDPV cases, they sometimes argue for reducing vaccinations. Nigeria is the reason why that is a bad idea. The number of cases in that country mushroomed dramatically in 2021 to 415. That happened despite a policy of continuing to vaccinate. Every child who contracted polio there was, by definition, not fully immunized. If we cut back on vaccination efforts, polio will run rampant around the globe and outbreaks in countries that haven’t had a case in decades will become routine in a few years.

We are incredibly close to eradicating polio once and for all. This horrible disease that leaves its victims paralyzed will go out kicking and screaming. Maintaining our commitment to complete eradication is essential. To help, visit endpolio.org.

Did you forget Rotary? The END POLIO NOW and PolioPlus initiatives have brought us to this remarkable place.